bcrowell.github.io

What’s the climb factor of your run?

I love mountain trail running because it’s simple and elemental. I don’t need fancy gear, and I’m directly tuned in to the natural world. Plus, how else are you going to get your feet this dirty?

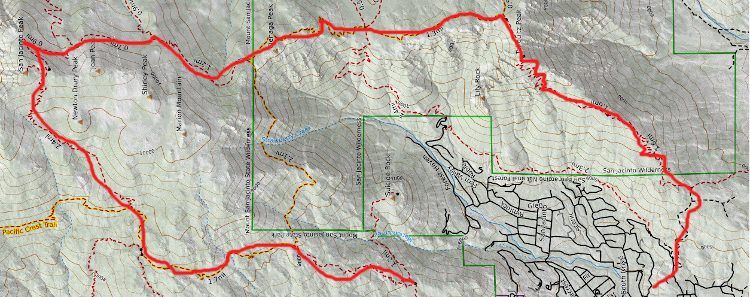

But there are good reasons to geek out about this sport when you’re at home on the couch. Here’s a map of one of my favorite summer trail runs in the San Jacinto Mountains. (If you want to see an actual usable map and description, there’s one here on trailrunproject.) When I first envisioned this loop, I wasn’t sure it was within my ability to do safely by myself. It’s not hard to work out the total mileage, and since the map is a topo, you can also figure out how much elevation gain there is. Those are the two numbers that people have traditionally looked at simply because they were easy to get off of a paper map, and if you’re curious what they are for this run, you can seem them on the trailrunproject page, where they’ve been calculated by a computer.

The problem is that those numbers don’t really tell you very much. The total distance is helpful, but the science shows us that total elevation gain isn’t really a useful measure of energy expenditure. It’s a natural thing that laypeople wonder about. For example, a reader of The Guardian wrote in to the “Notes and Queries” column to ask, “Is running up and down a hill better for you than running on the flat? Or does the downhill bit being easier counteract the uphill bit? What about running down a hill and then up, when you’re already tired?” Well, the part about “better for you” is something I don’t really care about, because I run for enjoyment, but anyway the underlying question is basically one about energy costs, which is the same one I need to know about in my own example, to gauge whether my endurance will be sufficient to get back to town.

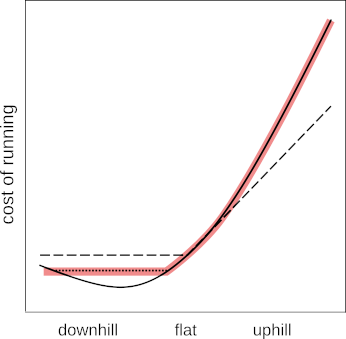

I’ve written a scientific paper on this topic, which may not be as entertaining as some of the cheeky British humor in the Guardian column. The related code and data are open source (1, 2). The TL;DR answer is that hill climbing is a highly nonlinear effect. For the relatively small slopes that most runners spend most of their time running on, the uphills and downhills come very close to cancelling out. However, on very steep mountain trails people aren’t efficient enough at running downhill to make up for the climbing.

This graph summarizes the results. The black dashed line with the hockey stick shape shows what you would think if you believed in total elevation gain as the right figure to pay attention to; in that model, downhill is the same as flat. The solid line is other people’s previous lab work with elite mountain runners on a tilting treadmill, breathing into a mask that measures their energy consumption. The curve highlighted in pink is the result of my work, in which I tried to find a model that would do a good job of describing real-world results from races. The cost of running downhill is indeed lower than the cost of running on the flats, but on very steep slopes the going is not as easy as you’d think from world-class athletes on a treadmill. The near-cancellation of uphills and downhills for less severe hills comes about because the middle portion of the pink graph is nearly a straight line.

Of course you can get smartphone apps and wearable consumer gadgets like the fitbit et al. that claim to tell you your energy consumption. The trouble is that these things use algorithms that aren’t public and probably not based on any valid science. And a wearable device won’t help you with planning for a future run.

It’s unfortunate that the scientifically validated figures aren’t as easy to figure out in your head as the traditional mileage-and-gain numbers, but I’ve written an open-source web-based app (also usable off-line) that will compute it for you if you upload a track. The track can be from someone else who’s hiked or run the route while carrying a GPS, or you can generate it with an application such as google maps or onthegomap. It will output a number that I call the climb factor of the run (CF), which is defined as the percentage of your energy used in hill-climbing, compared to a flat course. So for example, if the CF is 50% for a 10 mile run, then the energy expenditure for the run is equivalent to 20 miles. If you’re thinking of attempting that run, then you just need to check whether you normally have enough endurance to run twenty miles on the flats.

Other applications:

-

Set a target time and splits on a course you’ve never run.

-

Compare trail races on an objective basis.

-

Measure results from training.

Ben Crowell, 2022 Nov. 15